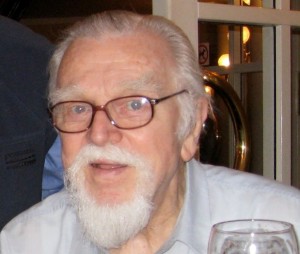

Neville Thiele, a former Vice President International of the AES, has died in Sydney, Australia, at the age of 91.

A Queenslander by birth, Neville was a friend to all who knew him, within the AES and outside, a great scholar, a fine engineer, a bushwalker and a man of peace.

“Born within the smell of the Castlemaine Four-X Brewery” as Neville cheerfully told everyone, he spent his childhood in the city of Brisbane, and its suburbs. His father, a qualified pharmacist, taught Neville and his brother Leonard core elements of confidence through his own passion for singing and poetry recital.

Document Copyright AES (Melbourne, Australia)

By the age of 12, Neville and his brother were experienced concert, choir and solo performers at their Milton State School and including engagements at the Theatre Royal amateur hours in Elizabeth St, Brisbane. Neville continued his education on a scholarship to Brisbane Grammar School.

In the 1930’s Brisbane radio was in its formative years exploring all manner of low cost entertainment including talent quests and children’s shows. Neville and Len were thus able to regularly broadcast songs and poetry their father had taught them. At this time Neville also became interested in the technology of these radio stations – simple affairs and very much hands-on. Being performers and so experiencing the reality of back-stage antics convinced these impressionable brothers of a desirable career direction as radio entertainers, and perhaps as broadcast engineers.

Radio performers needed to hone their vocal skills, particularly when the vernacular of the Queensland accent was present, and budding artists also needed to improve the quality of their recordings. This required audio equipment. At this time Neville’s interest in electronics became increasingly dominant. He made a resistance type microphone based on the 1924 design Reisz Laboratorium (Berlin) microphones of the young engineer Georg Neumann and pressed into service a combination of an amplifier driving (not amplifying) a gramophone pick-up and an Edison gramophone player mechanism with lead screw, as a recorder. One of his microphones and some of these recordings still survive.

Helped by Neville, Len went on to a distinguished career in entertainment, making the transition to television, and ultimately film, along the way. (He changed the spelling of his name to Leonard Teale in response to market pressures!). Neville was to support live theatre actively all his life taking lead roles in some amateur dramatic productions.

Equipment costs money. By this time, Neville was earning some as a junior clerk in the Commonwealth Bank. But times were tough. Neville took to designing equipment on paper as best he could and through experiment before committing funds. This habit was to last for the whole of his life. He meticulously maintained records of his work, ideas and experiments. A series of over 80 foolscap volumes survives to describe his personal thoughts during his years at EMI and ABC.

It was during this time that Neville became fascinated with the possibility of electrical equaliser networks improving the quality of their recordings. By 1942 he developed and was to ready to communicate the first of his ideas, the bridged-T equaliser in the local Amalgamated Wireless, Australia (AWA) publication Radiotronics.

Neville wanted training in electrical engineering. His then employer, the bank, wanted actuaries. The compromise was an evening course at Queensland University in mathematics but with a major in economics and with accounting included – an arts degree. This mix was destined not to last, however it did provide access to the undergraduate theatre culture, thus sustaining Neville’s enthusiasm for the performing arts.

One day without warning the bank announced to Neville that he was to be posted to a bank branch in Mackay (1000 miles away). Neville survived this apparently unprovoked attack as he was then supporting his mother in Brisbane. He later surmised that the combination of the undergraduate left wing tendencies of university reviews and the people they attract, together with the misfortune of having taken a liking to the daughter of a Major in Military Intelligence charged with fighting subversion had sealed his fate for the following twenty years.

By this time, Australia had joined the war. Neville enlisted and was immediately posted to an infantry battalion as a machine gunner. He likened this posting to being given a target tattoo and waving a football rattle at the enemy. Fortunately, Neville’s skills in diagnosing and fixing faults in telecommunications equipment on the spot were recognised and he became a signals technician despite central command repeatedly demanding he be returned to the original posting.

The experience of war and in particular the shooting of enemy soldiers at close quarters had a profound and lasting effect on Neville. The latter was to haunt him for the rest of his days, and he would make frequent reference to these acts of cruelty in moments of reflection, yet throughout his life outwardly displayed his engaging sparkle and a finely honed sense of the ridiculous.

By now Neville was also firmly convinced that he would not return from the war and so lived each and every day as a bonus while remaining vigilant against remote, disingenuous command.

On return from war service in New Guinea, fate introduced Neville to Lexie (they had almost met at the same primary school). After an extended internationally based courtship they married. They raised two wonderful children and Lexie independently achieved fame as an artist. At the end of the war Neville applied for and received a Commonwealth Reconstruction Training Scheme (CRTS) scholarship. This time the venue was University of Sydney and the course was engineering.

Engineering held a strong attraction for Neville, as did his well-established interest in the theatre. Both Neville and his like-minded study partner Doug Lampard actively involved themselves in Sydney University reviews. In those days they and their team had to do everything, becoming writers, producers, performers and, quite often critics. The interest was so strong that the pair failed to meet the Dean’s requirements in second year but, thankfully, were given a year to redeem themselves. Doug Lampard later went on to become the professor of electrical engineering at Monash University.

It was whilst studying for their degrees at the University of Sydney, Doug insisted that Neville come over and have a look at a new computing machine at the university that had some interesting features. This was the CSIRAC programmable computer featuring dynamic mercury delay line memory then being used by Trevor Pearcey and his team, ostensibly for cloud seeding studies. As processing on this machine could be slow, a loudspeaker had been added to signal either the end of processing or, alternately, an error. As a result the machine was later redeployed to Melbourne University physics department where it was used as one of the earliest programmable music synthesisers. At this time the composer Percy Grainger was in residence at the nearby conservatory. Grainger must have walked past the machine many times as he went to and from the cafeteria but the two never met. This machine is presently preserved in the Melbourne museum.

Neville graduated Bachelor of Engineering (Mechanical and Electrical) in 1952 and joined E.M.I. (Australia) Ltd. as a design engineer on special projects, including projects involving classified material.

With the start of television in Australia imminent, Neville spent six months of 1955 in the UK laboratories of EMI at Hayes, Middlesex, and at associated companies in Scandinavia and the United States. On return to Australia, Neville led the design team that developed EMI’s earliest Australian television receivers. However, when new ideas were mooted, management was not greatly interested. So, in 1959 when the young engineer suggested a new approach to loudspeaker design it was largely ignored by EMI.

Whilst at EMI UK. Neville was given the task of reviewing the patents of Alan Dower Blumlein with a view to claiming an allowed extension based on commercial worth to EMI. This was a dry legal process that was well away from the core intent of the patent process for making new ideas widely available in return for short term monopoly. Neville thus established an aversion to the patenting process which lasted for many years. In 2000 Neville applied for and was granted his first patent on his notched crossovers and subsequently licensed the technology to major international companies for digital and analogue implementations (US 6,854,005).

The general rejection by EMI to Neville’s new ideas marked a pivotal point in his career. Neville summarily published the first of his rejected yet seminal papers on loudspeaker parameters in the Proceedings of the Institution of Radio and Electronics Engineers Australia in August 1961, then immediately went for an interview for a position in the Studies and Design Laboratory of the ABC.

Joining the Australian Broadcasting Commission (subsequently Corporation) in 1962, he was engaged as Senior Engineer, Design and Development involving design and assessment of equipment and systems for sound and television broadcasting. Dogged persistence had made him a broadcast engineer.

It was in 1964, during Neville’s early years at the ABC , that a young Californian engineer, Richard Small arrived at Sydney University wishing to study for a PhD on loudspeakers. The two men were introduced and they began a collaboration which would lead to the “Thiele-Small Parameters” for the design of loudspeakers and their enclosures. Dick and Neville became celebrities in the audio industry, and were presented with medals and honours all over the world.

After acting as Director of Engineering ACT (Australian Capital Territories) responsible for engineering of the ABC’s radio and television studios in Canberra, Neville was, in 1978, appointed Assistant Director Engineering NSW (TV), responsible for engineering of the ABC’s Gore Hill television studios in Sydney.

In 1980 he was appointed Director, Engineering Development and New Systems Applications, where he was responsible for the ABC’s engineering research and development until his retirement at the end of 1985.

Neville was an avid bushwalker throughout his life. He spent many happy summer days trekking the wilds of Kosciuszko National park and visiting the summit, often whilst his wife Lexie attended painting and art camps in nearby Charlotte’s Pass.

Neville gave generously of his time. He was involved in national and international broadcasting standards, was a member of five of the seven committees advising the Australian Broadcasting Control Board on standards for the introduction of Australia’s colour television service (1969 to 1974), was Chairman of the Working Party on the Standard Demodulator. In 1980, and subsequently in 1981, 1983 and 1985 he represented Australia at international standards for sound and television broadcasting with the International Radio Consultative Committee (CCIR) of the International Telecommunications Union (ITU) in Geneva. He was an active member, too, of CCIR Interim Working Parties on International Exchange of Sound Programmes, Subjective Testing of Television Picture Quality, and High Definition Television.

At the 1985 meeting, he was appointed Chairman of CCIR Sub Working Group CMTT-C-1 on Long Distance Transmission of Analogue Sound, and was an active member of the Australian National Study Group 6 (Sound and Television Broadcasting), and ITU’s Radiocommunications Bureau, which succeeded the CCIR.

Neville was also involved in standards for Electroacoustics, nationally on committees of Standards Australia (SA), where he was Chairman of its Committee TE/8, Sound and Television Engineering and Recording, and Committee IT/1/29 on Information Technology. International committee duties included the International Electrotechnical Commission (IEC), and the Audio Engineering Society, concerned with loudspeakers and digital audio.

He was a Member of the Society of Motion Picture and Television Engineers and a Fellow of the Institution of Engineers Australia, and of the Audio Engineering Society of which he was Vice President, International Region from 1991 to 1993 and again from 2001 to 2005. During this time he actively promoted the establishment of the Chinese chapter of the AES. He was President of the Institution of Radio and Electronics Engineers Australia from 1986 to 1988.

Neville published more than thirty papers on electro-acoustics, network theory, testing methods and sound and vision broadcasting, and there are many more amongst his as yet unpublished works that did not meet his standards for clarity of expression.

Some of his papers, notably on loudspeakers, television testing and coaxial cable equalisation, have become accepted internationally as references on these topics, including origination of the Thiele-Small parameters for measuring and designing loudspeakers, and an intermodulation test, the Total Difference-Frequency Distortion measurement of audio transmission and recording.

In 1991, he was appointed Honorary Visiting Fellow at the University of New South Wales, and in 1994 was made an Honorary Associate at the University of Sydney, where he taught part-time in the Graduate Audio Program until he was 89 (2010).

In 1968 and again in 1992 he was awarded the Norman W.V.Hayes Medal of the Institution of Radio and Electronics Engineers Australia (IREE) for best paper published that year in the Institution’s Proceedings. In 1976 he was invited by the Audio Engineering Society (AES) to lecture on loudspeaker design at a seminar at the University of Colorado, a convention, and meetings of the AES throughout the United States. In 1994, he was awarded the Silver Medal of the AES for pioneering work in loudspeaker simulation.

In 2003 Neville and Richard Small jointly received the IEEE Masaru Ibuka Consumer Electronics Award for their work on loudspeakers. In that same year, Neville was awarded the Medal of the Order of Australia for services to audio engineering. In 2004 the IREE (Institution of Radio and Electronic Engineers, Australia, now Institute of Engineers) named their most prestigious award recognising eminence in information, telecommunications and electronic engineering the “Neville Thiele Award”. In 2008 Neville was awarded an Honorary doctorate by the University of Sydney, and in 2009 the Peter Barnett Memorial Award of the (British) Institute of Acoustics.

Neville is survived by his wife Lexie, son Laurence, daughter Miranda, seven grandchildren and two great-grandchildren, to whom we send our sincere condolences and with whom we all share our grief at the loss of a wonderful friend and colleague.

Written by Neville’s colleagues Graeme Huon (Australia) and Neil Gilchrist ( UK)

in response to a request from AES NY

Document Copyright AES (Melbourne, Australia)